John Ruskin Art and Craft Movement William Morris Craft Movement

Arts and Crafts: an introduction

The nascence of the Arts and crafts movement in Great britain in the late 19th century marked the outset of a alter in the value club placed on how things were made. This was a reaction to not only the damaging effects of industrialisation simply also the relatively depression status of the decorative arts. Arts and Crafts reformed the design and manufacture of everything from buildings to jewellery.

Fine fine art is that in which the manus, the head, and the eye of man become together.

John Ruskin, 'The Cestus of Aglaia, the Queen of the Air', 1870

In Great britain the damaging effects of car-dominated production on both social conditions and the quality of manufactured goods had been recognised since around 1840. Only it was not until the 1860s and '70s that new approaches in compages and design were championed in an try to correct the problem. The Arts and Crafts movement in Britain was born out of an increasing understanding that order needed to prefer a dissimilar set of priorities in relation to the industry of objects. Its leaders wanted to develop products that not only had more than integrity just which were likewise made in a less dehumanising way.

Structured more by a prepare of ethics than a prescriptive style, the Movement took its proper name from the Craft Exhibition Society, a group founded in London in 1887 that had as its starting time president the creative person and book illustrator Walter Crane. The Society'southward chief aim was to assert a new public relevance for the piece of work of decorative artists (historically they had been given far less exposure than the work of painters and sculptors). The Great Exhibition of 1851 and a few spaces such as the Refreshment Rooms of the South Kensington Museum (later on known every bit the 5&A) in the 1860s had given decorative artists the take a chance to show their work publicly, but without a regular showcase they were struggling to exert influence and to reach potential customers.

The Arts and crafts Exhibition Society mounted its start annual exhibition in 1888, showing examples of piece of work it hoped would help raise both the social and intellectual condition of crafts including ceramics, textiles, metalwork and furniture. Its members publicly rejected the excessive ornamentation and ignorance of materials, which many objects in the Great Exhibition of 1851 had been criticised for. For many years in Britain exhibitions mounted by the Lodge were the only public platform for the decorative arts, and were critical in irresolute the fashion people looked at manufactured objects.

Although it was known by a unmarried name (i that wasn't in fact used widely until the early 20th century), the Arts and crafts movement was in fact comprised of a number of dissimilar artistic societies, such equally the Exhibition Guild, the Arts Workers Social club (set up in 1884), and other craftspeople in both small-scale workshops and large manufacturing companies.

Many of the people who became involved in the Motility were influenced by the piece of work of the designer William Morris, who by the 1880s had become an internationally renowned and commercially successful designer and manufacturer.

Morris only became actively involved with the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Order a number of years after information technology was set upward (betwixt 1891 and his death in 1896), but his ideas were hugely influential to the generation of decorative artists whose work it helped publicise. Morris believed passionately in the importance of creating beautiful, well-made objects that could be used in everyday life, and that were produced in a fashion that allowed their makers to remain connected both with their product and with other people. Looking to the by, especially the medieval menses, for simpler and better models for both living and production, Morris argued for the return to a organisation of manufacture based on small-scale workshops.

Morris was not entirely against the use of machines, just felt that the segmentation of labour – a system designed to increment efficiency, in which the manufacture of an object was broken into pocket-sized, separate tasks, meaning individuals had a very weak relationship with the results of their labour – was a motility in the incorrect direction.

Similar many idealistic, educated men of his era, he was shocked by the social and environmental impact of the factory-based system of production that Victorian Britain had then energetically embraced. He wanted to free the working classes from the frustration of a working twenty-four hours focused solely on repetitive tasks, and allow them the pleasure of arts and crafts-based production in which they would engage straight with the creative process from beginning to end.

Morris was himself inspired by the ideas of the Victorian era'southward leading art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), whose piece of work had suggested a link betwixt a nation's social health and the way in which its goods were produced. Ruskin argued that separating the human action of designing from the act of making was both socially and aesthetically damaging. The Arts and crafts motion was likewise influenced by the work of Augustus Pugin (1812–1852). An interior designer and architect, Pugin was a Gothic revivalist and a member of the Design Reform Movement. He had helped claiming the mid-Victorian manner for ornamentation, and, like Morris, focused on the medieval period as an ideal template for both good pattern and practiced living.

In the final decade of the 19th century and into the 20th, the Craft motility flourished in big cities throughout the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, including London, Birmingham, Manchester, Edinburgh and Glasgow. These urban centres had the infrastructure, organisations and wealthy patrons it needed to gather pace. Exhibition societies inspired past the original one in London helped establish the Motion's public identity and gave it a forum for discussion. Members of the Craft community felt driven to spread their message, convinced that a better system of pattern of manufacture could actively change people's lives. Between 1895 and 1905 this strong sense of social purpose drove the cosmos of over a hundred organisations and guilds that centred on Arts and Crafts principles in Uk.

Progressive new art schools and technical colleges in London, Glasgow and Birmingham encouraged the development of both workshops and individual makers, too as the revival of techniques, including enamelling, embroidery and calligraphy. Craft designers too forged new relationships with manufacturers that enabled them to sell their goods through shops in London such equally Morris & Co. (William Morris'south 'all nether ane roof' store on Oxford Street), Heal'southward and Liberty. This commercial distribution helped the Move's ideas reach a much wider audience.

A particular feature of the Craft motion was that a large proportion of its leading figures had trained equally architects. This common civilisation helped develop a commonage belief in the importance of designing objects for a 'total' interior: a space in which architecture, furniture, wall decoration, etc. blended in a harmonious whole. As a effect, most Arts and Crafts designers worked across an unusually broad range of different disciplines. In a single career someone could apply craft-based principles to the design of things as varied as armchairs and glassware. Arts and Crafts also had a significant impact on compages. Figures including Philip Webb, Edwin Lutyens, Charles Voysey and William Lethaby quietly revolutionised domestic space in buildings that referenced both regional and historical traditions.

Although the Craft movement evolved in the metropolis, at its heart was nostalgia for rural traditions and 'the simple life', which meant that living and working in the countryside was the platonic to which many of its artists aspired. Increasingly, many left the city to constitute new ways of living and working, with workshops set up upwards across Britain in locations including the Cotswolds, the Lake District, Sussex and Cornwall. All these places offered picturesque landscapes, an existing civilisation of arts and crafts skills and, importantly, rail links for access to patrons and the London market.

Arts and Crafts makers based in rural communities both revived craft traditions and created employment for local people. This kind of development meant that the Movement endured longer in the countryside than in the metropolis, and had a more than significant touch on on the rural than the urban economic system. Significantly, the Craft community was open to the efforts of not-professionals, encouraging the interest of amateurs and students through organisations such as the Home Arts and Industries Clan. And it also created an surround in which, for the starting time time, women likewise equally men could begin to take an active role in developing new forms of blueprint, both every bit makers and consumers.

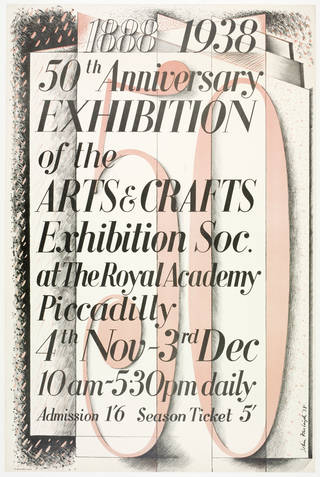

In Europe the honesty of expression in Craft work was a catalyst for the radical forms of Modernism, whereas in U.k. the progressive impetus of the Motion began to lose momentum subsequently the Beginning World State of war. Under the control of older artists it had begun to withdraw from productive relationships with manufacture and into a purist celebration of the handmade. Some organisations sympathetic to Arts and Crafts ethics did survive, peculiarly in the countryside, and the original Arts and crafts Exhibition Lodge mounted regular shows upwards to and beyond its 50th ceremony in 1938. In 1960, t he Society merged with the Cambridgeshire Guild of Craftsmen to form the Society of Designer Craftsmen, which is still active today.

Find more most Arts & Crafts.

Source: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/arts-and-crafts-an-introduction

0 Response to "John Ruskin Art and Craft Movement William Morris Craft Movement"

Post a Comment